There’s no denying the Woodville women were a fine-looking lot. Elizabeth Woodville was said to have used her beauty and maybe some feminine sorcery, to ensnare the king, Edward IV into an illicit marriage.

Richard Neville alias Warwick the Kingmaker was not happy. He was busy at the time negotiating a marriage for Edward with either Anne of France or Bona of Savoy in an attempt to strengthen ties with Louis XI of France, and any way what about Eleanor Talbot (Butler/Boteler) with whom there was supposedly a ‘contract of marriage’ or Elizabeth Lucy (Waite) his long standing mistress who also possessed a pre-contract. Ah well, these things happen.

Edward and Elizabeth’s union produced five daughters who survived to adulthood and two sons, the unfortunate Princes murdered in the Tower of London. The whole family is portrayed in stained-glass in the Royal Window in the northwest transept of Canterbury Cathedral. The original 1483-84 version was damaged during the 1640s, and the one on view today is a modern replica. The image of Cecily, kneeling between her sisters Elizabeth and Anne is now held by the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

Cecily was born on March 20, 1469 at the Palace of Westminster, the third of Edward and Elizabeth’s children. Before her second birthday Cecily was with her pregnant mother and sisters as they sought sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. In due course she would be stripped of her royal status and declared a bastard.

But as the crown bounced back and forth between the warring royal cousins, daughters were an important commodity during the turbulent times of the fifteenth century and Sir Thomas More pretty much summed up her life when he described Cecily as ‘not so fortunate as fair.’

By the time she was just five years old, Cecily had been betrothed to first James III’s son and heir and then to the Scottish king’s brother Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany. Neither of these betrothals came to fruition and in 1485 she was briefly married to Ralph Scrope of Upsall, a marriage arranged by her uncle Richard, who had by then declared himself king.

But later that same year the exiled Henry Tudor returned, seized the crown and married Cecily’s elder sister Elizabeth, so it was goodbye Ralph. The marriage was promptly annulled and Cecily was lined up for another dynastically advantageous marriage – and this is where the St John family link comes in.

During the winter of 1487/88 Cecily married John Welles, 1st Viscount Welles KG. John was the son of Margaret Beauchamp and her third husband Leo (Lionel) Welles, 6th Baron Welles. John was half-brother to Margaret Beaufort (and also to her St John half siblings) and therefore the King’s uncle of the half blood. John had received his returning uncle when he landed at Milford Haven in Pembrokeshire on August 7, 1485, and was knighted that same day. He went on to fight alongside Henry at the Battle of Bosworth, so his credentials were pretty sound.

Was this marriage a happy one? To be honest I don’t think happiness was a big consideration for a woman in Cecily’s position. Cecily was 18 at the time of her marriage and John approximately twenty years her senior. The couple had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anne, both of whom died young.

Cecily made frequent appearances at court, as befitted the daughter of one king and the sister-in-law of another and one who had a dodgy claim to the throne, it has to be said. In 1486 she carried her baby nephew Arthur to his christening and the following year she was one of the attendants at her sister’s coronation as Queen Consort.

But then in 1499 John Welles died and following a short period of widowhood Cecily decided when she married again it would be to a man of her own choosing. The date of her marriage to Thomas Kyme is not accurately recorded, but is believed to have taken place between May 1502 and January 1504 and without Royal License and boy was Henry displeased when he found out. He promptly banished her from court and confiscated her land.

Margaret Beaufort, the King’s Mother, championed Cecily’s case and allowed the couple the use of her home, Collyweston Palace. The marriage was a short one. Cecily, Princess of York died on August 24, 1507. Yet despite her high status, there are still a lot of unanswered questions about Cecily’s life and death.

Some sources claim that Cecily went on to have two children with Thomas Kyme, but as their existence was not ‘discovered’ until the 17th century, this seems unlikely. Thomas Kyme (or Kymbe or perhaps Keme) is described as a Lincolnshire gentleman, but an estate on the Isle of Wight also figures in their story. In fact, there is a legend that Cecily died at East Standen on the Isle of Wight and was buried at Quarr Abbey. However, there is evidence that she most likely died at a property in Hatfield owned by Margaret Beaufort where she had been staying for several weeks before her death. Margaret’s household accounts indicate that she paid most of Cecily’s funeral expenses at “the friars,” – could this be King’s Langley, a Dominican priory in Hertfordshire with a family connection and where Edmund of Langley, Duke of York was buried in 1402?

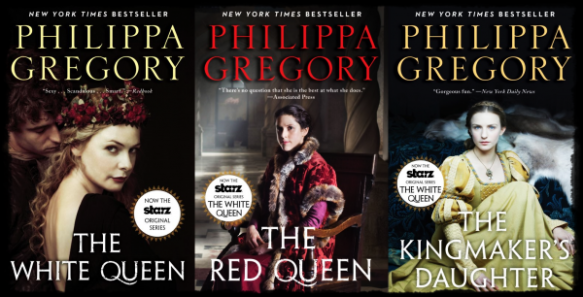

You’d really think there would be more concrete evidence about the lives of these women. I suppose that’s why such characters are much loved by historical novelists as they can invent the unknown bits.

So, there we have it – Cecily, Princess of York and another connection to the fascinating St John family from Lydiard Park.

The Royal Window – Canterbury Cathedral published courtesy of Casey and Sonja

Cecily, Princess of York

Margaret Beaufort’s tomb in Westminster Abbey

Elizabeth Woodville, Edward IV’s Queen.

Lady Margaret Beauchamp published courtesy of Duncan and Mandy Ball