Have you ever heard of the 17th century poet and dramatist Anne Wharton? No, neither had I.

The only work published during her lifetime was an elegy to her uncle John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester. After her death there was a short period during which her work was celebrated, but after that she was largely forgotten until in 1997 when Germaine Greer and Susan Hastings edited a publication called The Surviving Works of Anne Wharton.

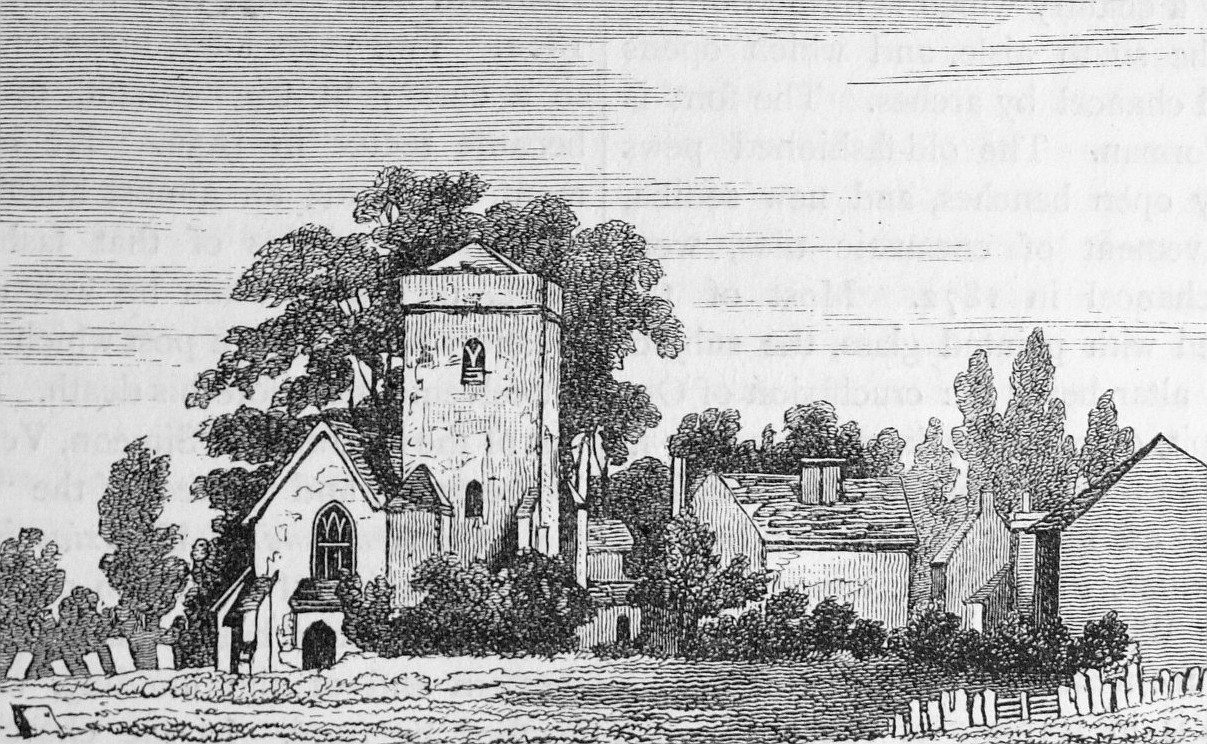

The younger of two daughters, Anne was born on July 20, 1659 after the death from smallpox of her father Sir Henry Lee, 3rd Baronet of Ditchley, Oxfordshire. She was baptised at All Saints Church, Spelsbury, Oxfordshire and her mother died just ten days later. The two little orphaned sisters were raised by their paternal grandmother, Anne Wilmot, Countess of Rochester.

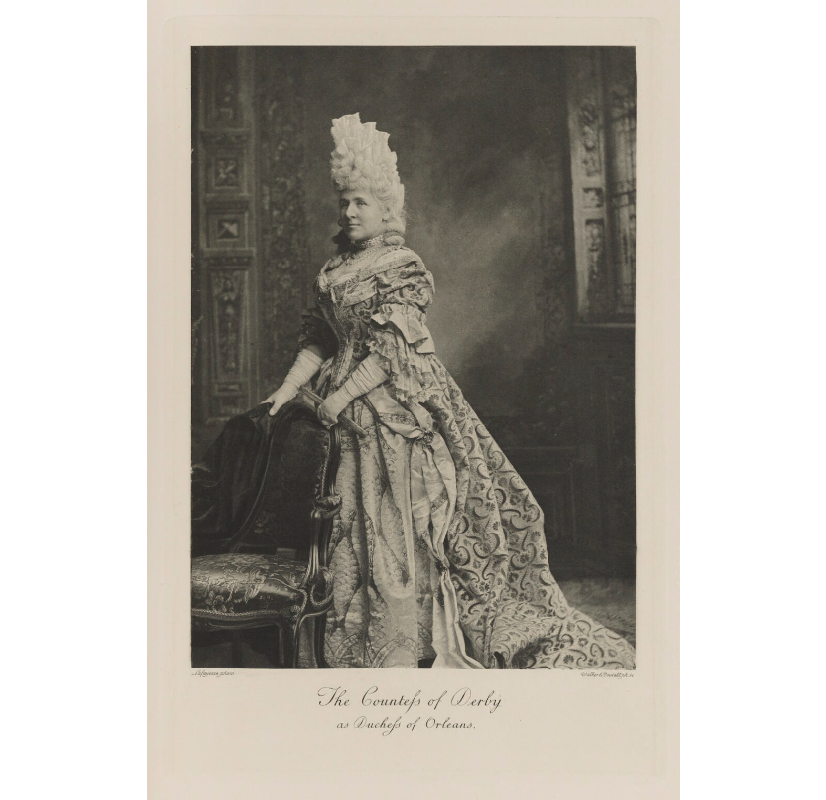

Anne, Mrs Wharton

In 1664 Anne, Countess of Rochester, was appointed Groom of the Stole to Anne Hyde, Duchess of York, the first wife of the King’s brother James. Until the death of the Duchess in 1671 Anne Rochester spent much of her time at court with her two little granddaughters in tow. A court described as “extravagantly and exhibitionistically licentious” by Greer and Hastings,

Anne and Eleanor received an education befitting their status, possibly joining the Princess Mary for French lessons at Court. They would have received lessons in music, dancing, writing and needlework and Anne was known to have spoken Italian.

When not at Court, the Countess of Rochester remained living at the home of her first husband, Sir Francis Henry Lee, in Ditchley with her extended Lee and Wilmot family.

By 1665 the sisters were living at the newly repaired and restored Wilmot family seat, Adderbury House, which had suffered under the occupation of parliamentarian troops during the Civil War.

The original house was small and Anne Wilmot remodelled the property in 1661 on which she is said to have spent £2,000. In a 1665 tax assessment there were 14 hearths recorded in the property and an inventory drawn up in 1678 lists Great and Small Halls, Drawing Room, Great Room above stairs, Great Square Chamber, Lesser Dining Parlour and eleven other rooms, excluding the offices.

Aged just 12 and 10 years old, Eleanor and Anne bought their first property under the supervision of their trustee Sir Ralph Verney, a 40 acre estate called Chelsea Park. The sisters had inherited a considerable fortune from their mother, Anne Danvers, making them each a very marriageable proposition.

Anne St John, Dowager Countess of Rochester

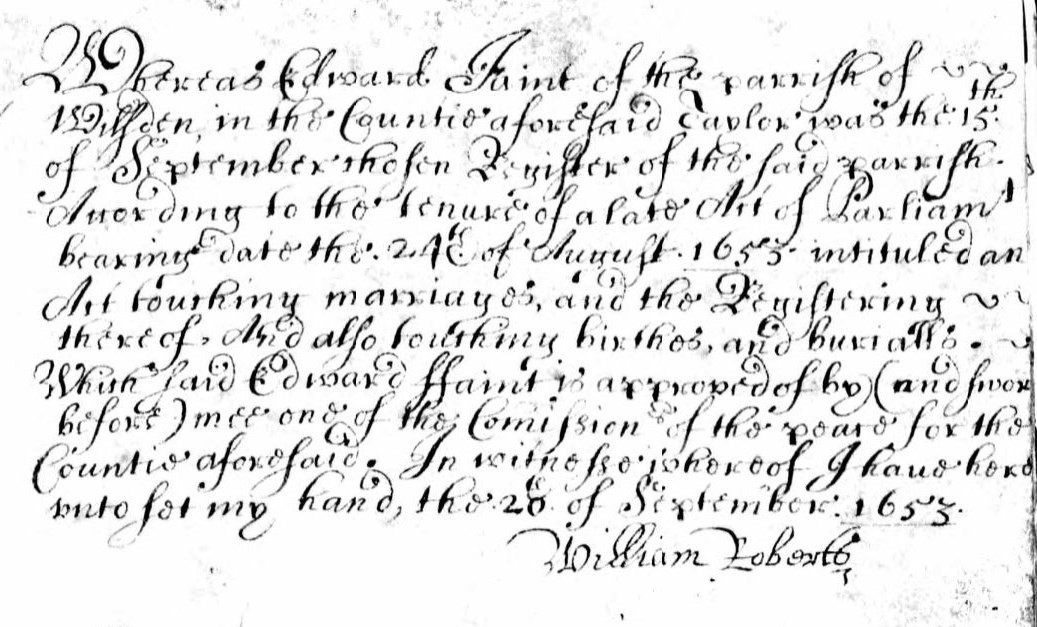

An entry in the parish registers of St Mary’s, Adderbury on September 16, 1673 records the marriage of the Honble Thomas Wharton Esq., eldest son of the Lord Wharton and Anne Lee, the younger daughter of Sir Henry Lee. Thomas was 25, Anne just 14 years old.

The minimum legal age at which a girl could marry in England was then 12 years old, although in practise this was unusual.

Anne’s husband Thomas Wharton had already earned a reputation as a rake and even her uncle, the licentious John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester was horrified that his mother was brokering a marriage with the profligate Whig politician, but perhaps Rochester had his own agenda.

Charles II wanted Anne to be married to a member of the Arundell family. Richard Arundell, 1st Baron Arundell of Trerice had served in the Royalist army during the Civil War and had fought at Edgehill and Lansdowne. He was raised to the peerage after the Restoration in recognition of the support he and his father had given Charles I. It was probably Richard’s son John the King had in mind for Anne.

But Lady Wilmot had set her sights on the fortune of Thomas Wharton. The irony of this is that Anne brought a dowry of £10,000 to the marriage and an income of £2,500 a year. On her death she left everything to Wharton.

Wharton was believed to have infected his young wife with syphilis, the great scourge of the 17th century, but Anne’s death sentence may have already been delivered before her marriage. After her death in 1685, her brother in law, Goodwin Wharton, wrote an explosive autobiographical expose. The manuscript was never published but is held by the British Museum.

Goodwin claimed that he had had an affair with Anne but that he had not been the only one. He wrote of how before her marriage (remember, aged 14) Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough, would bribe a servant to admit him into the bedroom Anne shared with her sister. He also claimed that Anne had ‘lain with long by her uncle, my Lord Rochester.’ It would seem likely that Anne had been abused and assaulted before her marriage and the candidates for infecting her with syphilis were several.

What kind of person was she? John Carswell author of The Old Cause: Three Biographical Studies in Whiggerism published in 1954, described her as a ‘demure, pious child’ while other accounts of Anne’s character have been somewhat derogatory and inaccurate and recorded to enhance the reputation of her husband. Considering her prominent position in court life she is something of a shadowy figure, seldom noted at social events when it could be safely assumed she was present. The only continuing interest in her appears to be in that of the inheritance she shared with her sister Eleanor, a battleground between their husband’s families and their grandmother Anne Rochester.

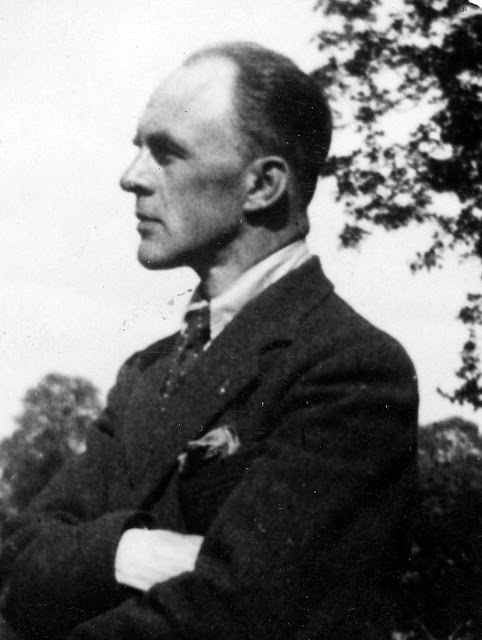

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl Rochester

There was evidence of Anne’s frail health even before she married. In August 1672 she went to Bath to take the treatments where she stayed for three months, a particularly long time which would have cost a considerable amount of money. Aged thirteen and just months before her wedding, Anne was suffering from a very sore throat. She soon began to experience problems with her eyes and in 1678 travelled to Paris for treatment. Two years later she returned to Paris suffering for convulsions (involuntary muscle spasms) which increased in frequency and severity.

Greer and Hastings propose a number of theories concerning Anne’s ill health, and make a convincing case that she was infected with syphilis long before her marriage to Wharton. However, they point out that her symptoms could also be attributable to epileptiform seizures, tuberculosis and even as a consequence of her medical treatment where mercury was commonly used.

Anne’s last days were spent wracked by convulsions and in great pain. She died at Adderbury on October 29, 1685 aged just 26 years old. She was buried in the Wharton family vault beneath the Chancel at St Mary Magdalen, Upper Winchendon.

Anne left £3,000 to Hester, John Wilmot’s daughter by the actress Elizabeth Barry, the rest of her fortune she left to her husband.

Thomas Wharton succeeded to the title Marquis of Wharton in 1715, some 30 years after Anne’s death. Anne’s correct title was therefore plain Mrs Wharton, not Marchioness of Wharton as she is frequently called in books and articles and which has caused confusion between other women named Anne in the Wharton family.

Even during her lifetime Anne enjoyed an extensive critical readership and the admiration of a network of professional writers including among them Aphra Behn. The first collected edition of her works was published in 1997 by Germaine Greer and Susan Hastings and in 2004 more work was discovered including 11 poems previously unknown.

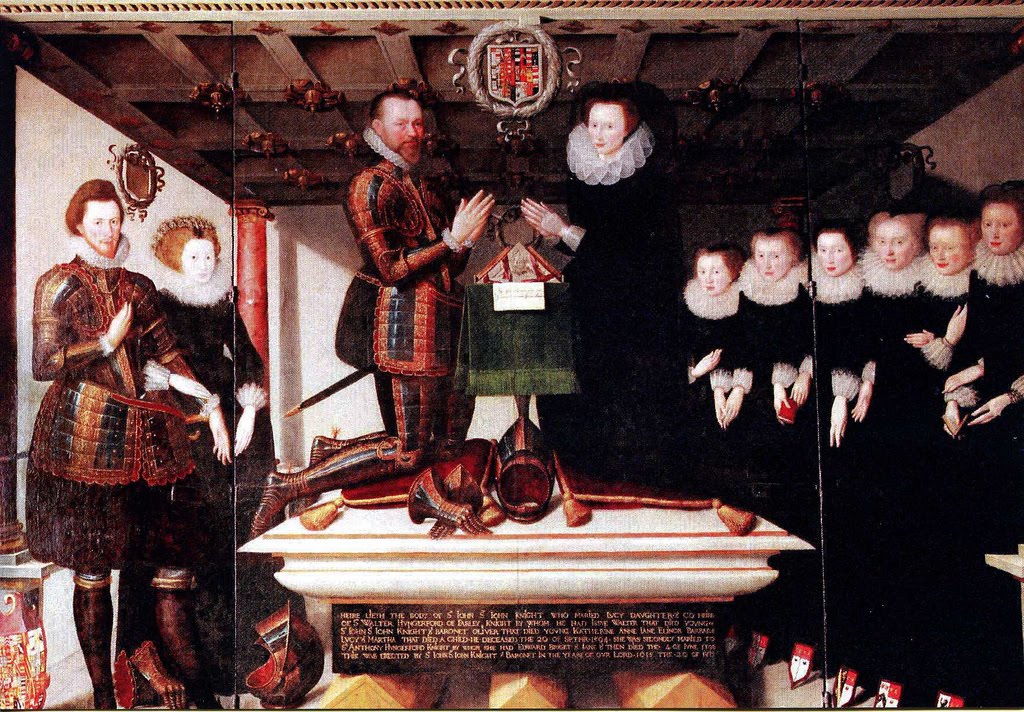

Sir Walter St John

So what is the connection to the St John family, although I’m sure you have probably worked it out by now. In the summer of 1664 Eleanor and Anne accompanied their grandmother on a visit to Lydiard Park where they stayed with Lady Rochester’s younger brother Sir Walter St. John. Sir Walter had been one of the trustees acting on behalf of the young Anne Lee during the marriage arrangements. Anne’s grandmother, Anne Wilmot, Countess of Rochester was the daughter of Sir John St John 1st Baronet, and his wife Anne Leighton who lived at Lydiard Park.

Reference:

The Surviving Works of Anne Wharton edited, with textual notes and commentary, by G. Greer & S. Hastings published by Stump Cross Books 1997

The St. John polyptych

The St. John polyptych Eleanor’s mother Jane St. John, third from right.

Eleanor’s mother Jane St. John, third from right.

![Photograph of Coleshill House, formerly in Berkshire [c 1930s-1980s] by John Piper 1903-1992](https://goodgentlewoman.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/coleshill-house.jpg)